Why most companies are stuck at the extremes—and the internal forces working against progress

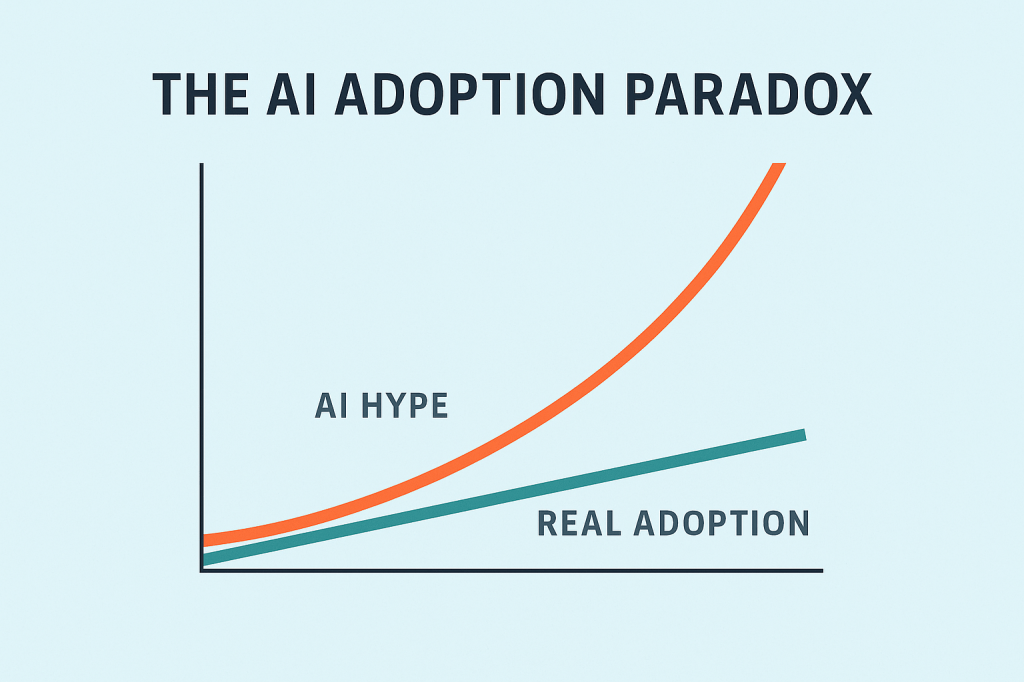

Something’s not adding up with AI adoption, and I think I’m starting to understand why.

Marc Zao-Sanders recently wrote in Harvard Business Review about how Gen AI usage in 2025 splits almost evenly between personal and professional applications. Meanwhile, executives everywhere are talking a big game—Jamie Dimon says JPMorgan has 450 AI use cases, and 44% of S&P 500 companies discussed AI on their recent earnings calls.

But here’s what bothers me: this narrative sounds nothing like what I’m seeing in the real world as a CEO.

The disconnect is stark. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, only 10% of firms are actually using AI in a meaningful way. Goldman Sachs has been tracking companies with the biggest potential AI upside, and their stock prices have been underperforming the market. As UBS put it bluntly: “Enterprise adoption has disappointed.”

So what’s really going on here?

The View from the Trenches

In my work leading an AI company and talking with organizations across different sectors, I’ve noticed something that explains this gap. Companies aren’t distributed across some normal adoption curve—they’re mostly clustered at two extremes.

On one side, I meet companies that think they’re AI geniuses. They’ve had a few successful individual projects and suddenly they’re convinced they understand everything about enterprise AI. They don’t want outside help. They’re going to build everything themselves.

On the other side are companies completely paralyzed by fear. They know AI matters, but they’re terrified of making the wrong move. They’ve read the horror stories and decided the safest move is no move at all.

What’s missing? Companies in the thoughtful middle—organizations that are realistic about both opportunities and the very real internal obstacles to adoption.

The Hidden Economic Forces at Work

Recent research from The Economist helps explain why this polarization exists, and it’s not just about technology complexity. The real barriers are economic and organizational, rooted in how power actually works inside companies.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: even when executives want to implement AI, they often don’t have the real authority to make it happen.

Think about it this way. On paper, a CEO can mandate organizational change. But in practice, the middle managers who understand day-to-day operations hold the real power. They can shape, delay, or quietly sabotage any initiative that threatens their position.

This isn’t new. Joel Mokyr at Northwestern University points out that “throughout history technological progress has run into a powerful foe: the purposeful self-interested resistance to new technology.” We’re seeing the same dynamics play out with AI.

Why People Resist (Even When It Makes Business Sense)

The resistance isn’t irrational—it’s perfectly logical from an individual perspective.

Take compliance teams. Their job is literally to stop people from doing risky things. With AI, there’s no established case law. Who’s liable if a model goes wrong? Close to half of companies in UBS surveys cite “compliance and regulatory concerns” as a main AI adoption challenge.

HR departments have grown 40% in the past decade. They’re worried about job displacement and employee relations. Why would they champion technology that might eliminate positions?

Middle managers face the biggest dilemma. As Steve Hsu from Michigan State University puts it, “If they use AI to automate jobs one rung below them, they worry that their jobs will be next.” So they find reasons why AI won’t work, can’t work, or shouldn’t work.

This creates what economists call “intra-firm battles”—and research shows these fights are real. Studies of factories in Pakistan found that employees actively misinformed owners about new technology that would reduce waste but slow down certain workers. Similar patterns emerged in Asian banks trying to automate operations.

The Board Governance Challenge Nobody’s Talking About

This is why the polarization I’m seeing makes perfect sense—and why it represents a critical governance failure. Most companies either:

- Overestimate their ability to overcome internal resistance (the “know-it-alls”), or

- Get overwhelmed by the complexity of organizational change and give up (the paralyzed)

Both miss the real challenge: AI adoption isn’t primarily a technology problem—it’s a board-level, company-wide governance and strategic oversight problem.

Here’s what boards need to understand: when your executives say they have “450 AI use cases” but only 10% of companies are using AI meaningfully, that’s not a technology gap—that’s a governance gap.

More fundamentally, it’s a strategic framing problem. Most organizations are treating AI as a tool or a series of discrete projects when it should be viewed as a company-wide transformational initiative. This misframing is at the root of both extremes I’m seeing.

The “know-it-all” companies think technical success equals organizational success. Their boards often hear about individual AI wins and assume they translate to enterprise transformation. But celebrating isolated AI projects while missing the broader organizational implications is like judging digital transformation by the number of computers you’ve bought.

The paralyzed companies see the organizational complexity and their boards conclude it’s too risky. But they’re treating AI as an optional add-on rather than recognizing it as a fundamental shift in how business gets done—like treating the internet as “just another marketing channel” in 1995.

What Boards Need to Do Differently

The few companies succeeding with AI at scale aren’t necessarily the most technically sophisticated. They’re the ones whose boards have developed governance frameworks that address both the strategic opportunities and the internal resistance dynamics.

As someone who’s served on boards and led AI implementation, I’ve seen what works—and what doesn’t. Successful AI governance isn’t about technical oversight; it’s about creating organizational conditions where rational resistance becomes rational adoption.

Here’s what boards should focus on:

Enterprise-Wide Strategic Integration. AI isn’t a department-level tool or a collection of pilot projects—it’s a company-wide capability that needs to be woven into the organizational fabric. Boards should insist on AI strategies that span all functions, not just IT initiatives.

Governance Framework Development. Don’t dismiss compliance and legal concerns—create board-level frameworks that let organizations experiment safely within clear boundaries. This requires treating AI governance as enterprise governance, not project management.

Cultural Transformation Oversight. The biggest barrier to AI adoption isn’t technical—it’s cultural. Boards need to oversee the cultural shift from “AI as a tool” to “AI as a way of doing business.” This means changing how people think about their roles, not just what software they use.

Strategic Incentive Alignment. Make middle managers part of the solution through board-mandated AI leadership roles. Instead of automating around them, give them new responsibilities that AI enables. This requires board oversight of organizational design, not just financial performance.

Staged Implementation Governance. Focus first on AI that enhances existing work rather than eliminating it. Build organizational confidence through wins before tackling harder transformation challenges. Boards should demand this phased approach rather than big-bang implementations.

Realistic Timeline Oversight. Enterprise AI transformation is a multi-year organizational change process, not a technology deployment project. Boards need to set appropriate expectations and maintain strategic patience while demanding measurable progress across all business functions, not just pilot programs.

The Board’s Strategic Opportunity

Market forces will eventually drive AI adoption, but boards that wait for market pressure are missing a strategic opportunity. As The Economist notes, this process will take longer than the AI industry wants to admit—the irony of labor-saving automation is that people often stand in the way.

But here’s what many boards don’t realize: the companies that figure out AI governance now will have sustainable competitive advantages long before market forces resolve the adoption lag.

For boards, this means recalibrating both expectations and oversight responsibilities. The question isn’t whether AI will transform your organization, but whether your board is providing the governance sophistication to manage that transformation effectively while competitors struggle with internal resistance.

The companies that figure this out won’t be the ones with the most AI tools—they’ll be the ones with the organizational sophistication to navigate internal resistance while maintaining momentum toward genuine transformation.

What This Means for Board Leadership

If you’re serving on boards or in board-level leadership, your role isn’t to become an AI technical expert. It’s to develop governance expertise in AI transformation—understanding how to oversee organizational change in the context of AI adoption.

The strategic questions boards should be asking:

- Are we treating AI as an enterprise transformation initiative or as a collection of departmental tools?

- How do we govern AI experimentation without stifling innovation or accepting unmanaged risk?

- What governance mechanisms help us identify and address rational resistance before it becomes organizational paralysis?

- How do we oversee incentive alignment across all departments—not just tech teams—to support strategic AI transformation?

- What board-level metrics actually indicate meaningful AI progress versus just AI activity or pilot proliferation?

The AI adoption story in 2025 isn’t really about technology capabilities—it’s about governance sophistication and the board’s role in managing the political economy of change within organizations.

Understanding that distinction might be the difference between joining the 10% of companies using AI meaningfully and staying stuck in the 90% that are still talking about it. More importantly, it’s the difference between boards that provide strategic value and those that simply monitor financial performance.

As someone who works with boards on AI governance challenges, I’m curious about your experience. How is your board approaching AI oversight? Are you seeing these same internal resistance patterns, and what governance frameworks are you developing to address them?

Sources:

“Why is AI so slow to spread? Economics can explain.” The Economist, 2025.

Zao-Sanders, Marc. “How People Are Really Using Gen AI in 2025.” Harvard Business Review, April 9, 2025.

Leave a comment